Evolution in the law of transport noise in England

October 1, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.103050

This article tracks the evolution of the regulatory framework in relation to transport noise in England from private and public nuisances in common law to the defence of statutory authority. The article looks at the evolution of transport noise law focusing primarily on the emergence of turnpike roads in the eighteenth century, railways in the nineteenth century, the extension of road motor vehicles in the verge of the twentieth century and, lastly, the introduction of jet aircraft after World War II. The introduction of these noise sources shaped the current noise regulatory framework in England. Traffic noise in England enjoys protection against nuisance claims. Nowadays, the British Parliament is reluctant to remove citizen’s private rights, and express statutory authority has appeared in very few legislative provisions, save when these have been juxtaposed with some form of statutory remedy —which was not present in early English jurisprudence on transport noise.

Josep Simona: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Josep M. Rossell: Supervision. Xavier Sánchez-Roemmele: Writing – review & editing. Marc Vallbé: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

J. SimonaDepartment of Mining, Industrial and ICT Engineering, Manresa School of Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Manresa, Spain. marc.vallbe@upc.edu , J.M. Rossell1, X. Sánchez-RoemmeleFASA MIOA MAAS MAES MIEEE, United Kingdom , and M. Vallbé1.

Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Volume 100, November 2021, 103050

Keywords: noise, transportation, law, regulations, england

Outline

| Highlights | |

| 1. Introduction | 4. Conclusions |

| 2. Methodology | Acknowledgements |

| 3. Review | References |

Highlights

- Evolution of the regulatory framework of transport noise in England.

- Turnpike roads and railways could not give rise to nuisance in law.

- Codes, including maximum noise levels, were introduced for road vehicles.

- No compensation remedy present in initial jurisprudence on transport noise.

- Current consensus is that statutory defence authority should be linked to compensation.

1. Introduction

Part of the current English legislation in transport noise is the result of the transposition of European Directives as a consequence of the United Kingdom’s (UK’s) membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) from 1 January 1973 to 31 January 2020 when it left the European Union (EU). Nevertheless, a substantial number of elements of current English policy and legislation predate this period.

Noise nuisance has been addressed by English common law since medieval times.The National Archives, 1302 Current judicial philosophy in relation to noise is already present in eighteenth century case law.Kerse, 1975, Lucas, 1989 citing Gearty, 1986 Statutory authority defence against noise claims originated in the same period.Bassford, 2007, Kerse, 1975, Wilde, 2017 The introduction of the railway in the early nineteenth century, of motor-vehicles in the late nineteenth century and of aircraft in the twentieth century —specifically, jet aircraft after World War II (WWII)— generated new distinguishable sources of noise which did not form part of the acoustic character of the country until they were introduced and, therefore, new noise problems which required having to interpret the law in view of these new transport noise sources.

There is extensive literature on the initial issues created by noise produced by new means of transport such as the railway in the early nineteenth century,Brenner, 1974, Jeans, 1875, Linden, 1966, Morgan, 2014, Pease, 1907, Smith and Wilde, 2010 and on the current noise policy and legislation in England.Abbott et al., 2015, Adams and McManus, 1994, Defra, 2010, European Commission, 2016, Kerse, 1975, Moor, 2011 However, this literature is usually presented specific to the current situation and to concrete issues at the time of publishing, rather than in a comprehensive way. It is therefore difficult to interpret why slightly different defences against noise claims are applied to different means of transport —railways, roads and aircraft—, and whether these defences have been interpreted in the same way in different periods. This paper intends to provide a clear and comprehensive review of the evolution of noise law in England, approaching rail, road and aircraft from their origin through their development, and to present.

This paper is targeted to the transport sector and any communities or professionals with an interest in assessing environmental impacts. It aims to respond, first, to whether the current interpretation of the law is the same as its original intent; and, second, whether the same laws apply to all forms of transport.

There is extensive literature on the effects of noise and on current noise legislation.Berglund et al., 1999, Berglund and Lindvall, 1995, WHO, 2018, WHO, 2009, WHO, 1980 Noise legislation in antiquity is referenced in scientific literature.García, 2006, Lucas, 1989 Nevertheless, our paper also includes the epic of Atrahasis, which is not commonly mentioned as the potential first reference to a noise complaint. There is also literature on statutory authority protection.Bassford, 2007, Brubaker, 1995, Moor, 2011 However, we have not found a comprehensive review considering each of the forms of transport from the times of the Canal Mania to the introduction of aircraft.

2. Methodology

Current and past regulations, case law and reports archived in The National Archives (London) as well as research articles and books on the topic of transport noise have been reviewed with the aim of clearly identifying how different concepts related to English law on noise evolved during history until nowadays. From a first group of documents covering different time frames and means of transport, snowball samplingGoodman, 1961 was used to identify further references to cover the gaps identified during the literature review. Information on early issues related to road motor noise was only found in hard copies of ministerial reports in The National Archives.

The structure of this paper is content-related clustering. To contextualise noise in human sociocultural evolution, the discussion in section 3.1 includes the first noise complaint ever recorded in ancient Mesopotamia. Notwithstanding, the focus of this article is on England and it therefore primarily draws from nineteenth and early and mid-twentieth century documents.

The article focuses on the evolution of the law in England to retain the references to a single regulatory framework. Most of the points discussed in this article are also applicable to the other countries in Great Britain, but some may not. London could be considered a distinctly differentiated area where some of the described points may not apply either.

In relation to other countries with a predominance of common law, it is notable that compensation is embedded in the United States of America’s Constitution through its Fifth Amendment.Linden, 1966 . In Canada, planning can deprive of both rights and compensation in regulated sectorsBrubaker, 1995 Therefore, the findings of this paper are not considered to be strictly applicable to these countries.

3. Review

3.1. “The first noise complaint ever recorded”

«The land grew extensive, The people numerous, The land was bellowing like a bull. At their din the god distressed. Enlil heard their cry. He addressed the great gods, The cry of mankind has become burdensome to me, Because of their din I am deprived of sleep».

These lines are part of Atrahasis, a Mesopotamian epic of the second millennia BC as translated by Lambert and Millard (1968) as cited in Moran (1971). In the epic, Enlil, a Mesopotamian man-like godMillard, 1966 wants to eliminate humankind due to the noise disturbance caused by people, which deprives him of sleep. “Bellowing like a bull”, “din” and “cry” are likely to have been used to describe noise in the epic’s text, although this is also considered to be ambiguous.Oden, 1981 It is however clear that the result is sleep disturbance.Millard, 1966, Oden, 1981 A second god, Enki, defends humankind since the order to exterminate humans “ignored all distinction between innocent and guilty”Moran, 1971 and helps Atrahasis’ group to avoid the extinction brought by the deluge —in a reminiscence of Noah’s Ark biblical narration. After the flood, a new order for mankind is planned on terms acceptable to Enlil.Moran, 1971

Independently of whether the Atrahasis’ epic actually features the first recorded reference to a noise complaint or not,Moran, 1971, Oden, 1981 it certainly contains modern elements of noise control. First, with the abatement of noise through the suppression of the source (humankind), later recognising noise as an inherent characteristic of society, and finally, agreeing that implementing noise mitigation measures (through new actions or rules) may be an acceptable compromise.

3.2. Early mention to noise in English law

In thirteenth century London, noisy or unsavoury trades – such as tanners, butchers and smiths – were restricted to specific areas of the city.Lucas, 1989 citing Tempest and Bryan, 1976 The National Archives contain a petition, dated as early as 1302, from the Franciscan friars of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk to King Edward I, to relocate the courthouse further away from the friars’ premises since “when it rains and it is stormy the people seek refuge for themselves and their horses in the church of the friars; at other times when they are assembled the friars are unable to say mass because of the noise and press of the people…”.The National Archives, 1302 The King attended the friars’ petition. This reveals that noise has long been regarded as a nuisance in English common law.

3.3. Non-transport noise in England in the early modern age

Noise as a common law nuisance is consolidated during the eighteenth century in its present form. The ringing of church bells is discussed in the case law Martin vs Nutkin (1724), 2P. Wms. 266.Kerse, 1975 The case law R v Smith (1725), 2 Str. 704 held that noise from a “speaking trumpet” was a public nuisance, and therefore a crime, when used at night.Lucas, 1989 citing Gearty, 1986 London Metropolitan PoliceUK Parliament, 1829 is considered to be the first modern police in England.Lyman, 1964 It was soon given powers to deal with anti-social behaviour through section LIV on the prohibition of nuisances by persons in the thoroughfaresUK Parliament, 1839 , which included noise in the streets and disturbance to inhabitants at their homes due to noise.

Section 23 of the Municipal Corporations Act 1882UK Parliament, 1882 gave powers to councils to make byelaws “for prevention and suppression of nuisances not already punishable in a summary manner by virtue of any Act in force throughout the borough”, and several local councils sent byelaws to the UK Secretary of State for their approval. Noise occupied a prominent position among nuisances not covered by any other Act, such as the Public Health Act 1875.UK Parliament, 1875 Thus, nuisances in the new proposed byelaws included: “Every person who… shouts… or disturbs the public peace”; “who sounds, beats, or plays” some musical instruments; “procession or assemblage of people which by loud singing, shouting, or bawling, or by drum, gong, wind or stringed musical instrument or other resonant thing, or by grotesque action or disorderly behaviour causes a nuisance to the inhabitants”. Of a list of 28 byelaws received by the UK Secretary of State between 1883 and 1886The National Archives, 1895 only 8 are classified as “allowed”. The rest are classified as “not proceeded with”, “not allowed”, “disallowed” or “objected”. The main reason for refusal was that it was considered that some of the proposed byelaws, such as Luton’s, could become a “restriction to liberty” since it could apply to the “Waits at Christmas”.A type of musical band in England and Scotland, which were abolished as a result of the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, but which remained over the Christmas period It continues: “The very fact that it is obviously directed against the Salvation Army is an objection”.The Salvation Army (TSA) is a Protestant Christian church. It has a tradition of having musicians available. Nevertheless, the refusal of byelaws to prevent musical religious processions was not totally effective since accounts of reports of disturbances due to using local byelaws against the Salvation Army appear on record.The Guardian, 1891 This exception continues in modern Britain where, in accordance with Section 79 of the Environmental Protection Act as modified by the Noise and Statutory Nuisance Act 1993, “noise made… (c) by a political demonstration or a demonstration supporting or opposing a cause or campaign” in a street is not a statutory nuisance.UK Parliament, 1990 as amended 1993 The intent of introducing noise limits to political protest through The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts BillUK Government, 2021 caused unrest in Bristol in March 2021.Casciani, 2021

3.4. Evolution of transport in England

Transport in medieval England included land, river and sea transport.Langdon and Claridge, 2011 Land transport made use of the once prevalent interconnected roads and bridges of Roman Britain, which had fallen into poor conditions by the Middle Ages.Newman, 2012 The network remained however suitable for a “low-loads” transport, based on the use of oxen, horses and mules travelling in file.Langdon and Claridge, 2011, Newman, 2012

Modern times saw the need for quicker transport able to carry heavier loads. This required improving and extending the transport network, first with the maintenance of roads and bridgesCooper, 2006](#b0075) , then with the expansion of ports and canals. The Highways Act 1555UK Parliament, 1555 imposed the burden for highways maintenance on local authorities, continuing the Anglo-Saxon “Trinoda necessitas” where highways maintenance was the collective responsibility of the inhabitants of an area rather than it being carried out by specialised labour.Webb and Webb, 1913 This became ineffective where relatively small communities did not have the means to maintain major ways, such as some communities along the route between London and Edinburgh. From the late seventeenth century, Parliament increasingly took responsibility for repairing and maintaining roads from local authorities.UK Parliament, 2010a This was done through Private Acts of Parliament in favour of Trusts which maintained roads in exchange for levying tolls. The eighteenth century saw both a canal maniaBoughey and Hadfield, 2012 and a turnpike road maniaUK Parliament, 2010a which resulted in better maintained roads, and consequently in faster transport. In the nineteenth century, interest in steam grew during the Napoleonic Wars due to a shortage of horses and an increase in the cost of feeding them.Alexander and Siton, 2018, Kirby, 1993 This resulted in a railway mania,UK Parliament, 2010b which added rail to the main means of transport. The start of the twentieth century saw the increase of road motor vehicles. After WWII, jet aircraft completed the main means of transport as we know them today.

3.5. The defence of statutory authority

The defence of statutory authority is a legal doctrine present in English law. It provides defence in civil or criminal proceedings for nuisance.Morgan, 2014 The defence applies to public officials or private corporations doing quasi-governmental tasks when they are exercising a task allowed by the legislature.Linden, 1966, Moor, 2011 This defence does not provide blanket immunity or carte blanche, which could exacerbate nuisances, but it requires reasonable care.Moor, 2011 It also takes account of a variety of considerations such as the specificity of the location, the inevitability of the nuisance, the effect on statutory provisions, and the bearing that negligence has on the defence.Moor, 2011

Linden (1966) identifies the evolution of the defence of statutory authority from medieval lords who could not be sued in their own courts. The notion that “the King could do no wrong”, has long been part of the common lawLinden, 1966 citing Holdsworth, History of English Law and Hapert and James), which then evolved to protecting public officials in the performance of public duty.Moor, 2011 cites Entick v. Carrington, 1765 as a case law which shows that such statutory authorization was evident at that time As Moor (2011) states, “Although the judgment in Entick failed to find such authority, it did acknowledge that Parliament could authorise such interferences with property rights by clear prescription; ‘if the Legislature be of that opinion they will make it lawful’. This eighteenth-century judgment may seem trivial, especially in the modern context of larger scale industrial nuisances and pollution cases, but it indicates the origins of greater state infringement on private property rights; something which was to continue over the following century.” The same statutory defence can apply to private enterprises when the authority has allowed them.

Brubaker (1995) citing Gimpel (1976) sets the origin of statutory defence for nuisances in medieval mining: “Medieval mining regulations provide some of the earliest examples of governments overriding common law property rights… in the thirteenth century… the governments encouraged miners to prospect on private property, allowed them to cut privately owned trees, and authorized them to divert streams. To ensure that the miners’ victims couldn’t fight back, the governments freed the miners from the jurisdiction of local magistrates.”

In relation to infrastructure, Bassford (2007) identifies the turnpike roads and harbours of the early eighteenth century as the first major infrastructure projects which required immunity from suits in nuisance, in order to install a toll for the use of a road or harbour dues respectively. In 1663, counties by the road between London to York and so into Scotland requested a levy toll. Webb & Webb (1913) state that “On this petition Parliament fell back on certain medieval precedents, and authorised, by a special statute… to erect gates and levy tolls … to devote this revenue to specially repairing the pars of the Great North Road within their respective jurisdictions.”

According to Webb & Webb (1913) “the Surveyor appointed by the new road authority is gradually invested with nearly all the powers of the Parish Surveyor of Highways… He is authorised summarily to suppress nuisance, and enabled to take compulsory without compensation from the common or wastes, within the parish or without, or out of any river or brook, whatever ‘gravel, chalk, sand or stones’ are needed for the mending or his road; and to resort for this purpose also to private grounds, on payment merely of the actual damage done.” Littleton, in 1692, proposed the use of charges as “Every person ought to contribute to the repair of roads in proportion to the use they make of, or the convenience which they derive from them.” The law relating to statutory authority would later be consolidated in cases primarily related to railways.

3.6. Railway noise and the consolidation of statutory defence

The first claim for nuisance on railways was from the turnpike roads, which had their own statutory defence authority. The first passenger railway line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway,Macauley, 1872 provides the first example of defence of statutory authority applied to nuisance arising from railways. Taking on the experience of turnpike roads, the Stockton and Darlington Railway was promoted through a Private Act, a parliamentary tool by which powers or benefits are passed to individuals or bodies (such as railways promoters) rather than to the general public. Parliament's role was to arbitrate between the promoters of these Private Acts and those affected by their projects, as well as to take account of the public interest. Private Acts allow to take over, for instance, a communal right of passage,UK Parliament, 2010c acquire land through compulsory purchaseUK Parliament, 2010a and provide a statutory defence against a nuisance claim, as explained in more detail below.

The Trustees of the Stockton and Barnard Castle Turnpike Road, as well as most of the agricultural community around the railway line, complained to the company running the railway that the locomotive engine frightened the horses, which constituted an intolerable nuisance, and requested that the use of locomotives be stopped. The case was heard in a criminal court in 1832. As cited by Jeans (1875) the following verdict was returned, which we reproduce in full due to its relevance:

“That the Act of Parliament empowered the company or persons authorised by them to use locomotive engines upon the railway; that the railway was made parallel and adjacent to the ancient highway; that it did not appear whether or not the line could have been made in this instance to pass at a greater distance; that the locomotive engines on the railway frightened the horses of persons using the highway as a carriage road; that the locomotives were of the best construction known at the time, and the defendants used due care and diligence in the management of them.”

The sentence was appealed and an additional judgement returned remarking:

“that an interference with the rights of the public must be taken to have been contemplated by the Legislature, since the works of the statute authorising the use of the engine were unqualified, and the public benefit derived from the railways (whether it would have excused the alleged nuisance at common law or not) showed at least that there was nothing unreasonable in the clause of the Act of Parliament giving such unqualified authority”.

For the rest of the nineteenth and part of the twentieth century, several cases known today as the ‘railway cases’, consolidated this view. These ‘railway cases’ were reviewed in Allen v Gulf Oil Refining Ltd 1981.Willberforce et al., 1980 They highlight the defence of statutory authority against nuisance claims and the duty of taking reasonable care (or not to act negligently). Hammersmith & City Railway Company v. Brand (1869), reaffirmed decisions in R v. Pearse (1832) and Vaughan v. The Taff Vale Railway Company (1860) in the terms that “where Parliament by express direction or by … implication has authorised the construction and use of an undertaking or works, … is authorised with immunity from any action based on nuisance.” Geddis v. Proprietors of the Bann Reservoir (1878) states “To this there is made qualification, or condition, that the statutory powers are exercised without negligence – that word here being used in a special sense so at to require the undertaker, as a condition of obtaining immunity from action, to carry out the work and conduct the operation with all reasonable regard and care for the interest of other persons.”

Although the defence of statutory authority and the duty of care for industries promoted through Private Acts are not typically challenged by Parliament or judges, there is greater discussion on whether immunity should be linked to compensation. Thus, Lord Edmund-Davies highlighted that “…the absence of compensation clauses from an Act conferring powers affords an important indication that the Act was not intended to authorise interference with private rights” and referred to Metropolitan Asylum District v. Hill (1881) 6 App. Cas. 193, at 203 and the other cases cited in Halsbury’s Laws of England, 4th Edition, Vol. 1, para 196. However, he stated: “But the indication is not conclusive (see Edgington v. Swindon Corporation (1939))” and gave support to the appeal, which did not link immunity to compensation.Willberforce et al., 1980 A different view was held by Lord Keith of Kinkel, who felt that the Gulf Oil Refining Ltd (the appellants) in Allen v Gulf Oil Refining Ltd 1981Willberforce et al., 1980 had only been given by Parliament the right to ‘compulsory purchase’ and that “The appellants failed to include in their Act any reference to authority to operate, work or use a refinery. If they had done so, Parliament might well have insisted on provision for compensation.” Lord Keith of Kinkel’s view was not supported by the other Lords.

The compensation issue was also commented in a most recent UK Supreme Court case, Coventry v. Lawrence (2014), where in section 90 Lord NeubergerNeuberger et al., 2014 was of the view that “it seems wrong in principle that, through the grant of a planning permission, a planning authority should be able to deprive a property owner of a right to object to what would otherwise be a nuisance, without providing her with compensation… This point is reinforced … the Planning Act 2008… expressly excludes claims in nuisance… and … provides for appropriate compensation where a neighbour would, but for section 158, have had a claim in nuisance. It is also to be noted that section 76 of the Civil Aviation Act 1982 expressly excludes an action for nuisance owing to aircraft, but section 1 of the Land Compensation Act 1973 provides for compensation for neighbours (including in respect of nuisance by noise attributable to aircraft) when land is developed as an ‘aerodrome’“.

3.7. Road vehicle noise

In this section we present a different case from that of railways. Road traffic noise in England enjoys statutory protection against nuisance claims. Motor cars were introduced at the end of the nineteenth century. The Locomotive Act 1861UK Parliament, 1861 includes the first speed limits for road vehicles: 10mph on any turnpike road or public highway and 5mph through any urban area. However, in the same way as railways originally encountered the opposition of canals and turnpike roads industries, road motor vehicles found the opposition of the railways and canals sectors. Extremely low speed limits (4mph on any turnpike road or public highway and 2mph through any city, town or village) and a requirement to have at least three drivers (one of them on foot at least 60 yards in front of the vehicle, carrying a red flag to warn riders and drivers of horses) were approved just four years later.UK Parliament, 1865 These unreasonably low speed limits and the use of a warden were lifted by the end the century. The warden was replaced by the obligation of an audible warning: “Every light locomotive [NB meaning every vehicle] shall carry a bell or other instrument capable of giving audible and sufficient warning…“.UK Parliament, 1896

The replacement of the warden by a bell or horn did not come without issues. As recorded by the Metropolitan Police in 1912,Henry, 1912 motor traffic noise became an issue due to the excessive use of horn and failure to use silencers on exhausts: “… complaints of unnecessary and nerve racking noise made at night by the drivers of motor vehicles… the Locomotives on Highways Act, 1896, and… the Motor Car (Use and Construction) Order, 1904, places upon drivers the obligation of giving an audible and sufficient sound by way of warning to other vehicles and pedestrians, with a view to preventing accidents…” However, the police commissioner writing the circular stated that drivers used the “audible warning…where there is no hidden danger, and where the only danger is attributable to reckless speed on part of the driver…thereby disturbing the rest of residents…”.Henry, 1912 The devices causing nuisance were the “cut-out”, prohibited by the Motor Cars (Use and Construction) Amendment Order 1912 (which introduced the requirement that escape gases passed through a silencer), and either electric horns or horns operated by the engine exhaust.Henry, 1912

The need to measure which silencers were most effective raised several questions – firstly, how to assess the “reduction in noise” provided by the silencers but, most importantly, how to actually measure sound. The first trials to set a standard were focused on silencers and under the initiative of private associations rather than the Government.

In 1913 the Auto-Cycle Union tested silencers both aurally and with audiometers.Kaye, 1935 In 1927 “Certificates of Performance” were issued as “Audiometer records” , which did not give any quantitative data relating to the motor cycle under test but compared the degree of noise made with other well-known sounds.Kaye, 1935

After the Motor Cars (Use and Construction) Amendment Order 1912, the publication of motor cars acts and regulations accelerated in the 1930s. The regulations focused on two parameters: the obligation of using a silencer and the driver’s behaviour. Section 76 (NB 75 in some references) stated that “No motor vehicle shall be used on a road in such manner as to cause any excessive noise which could have been avoided by the exercise of reasonable care on the part of the driver.”

Trespassing was an issue that the police encountered when enforcing the above provisions. In a letter dated in 1934, it is stated that “A constable inspecting a silencer … if he touches the vehicle he commits a technical trespass, and if he touches its driver, he commits a technical assault”.The National Archives, 1949

As road vehicles became more popular over the years, the police highlighted that the issue was not the individual vehicles, unless the driver behaved unreasonably – it was the flow of traffic. A first example is shown in a series of letters dated 1936 The National Archives, 1949 where the reverend of a church located next to a “junction of three main roads” complained “that his congregation is disturbed by noisy motor cycles”. The response of the Secretary of State illustrated the principle of best practicable means/reasonability: “It would appear inevitable … traffic should cause a certain degree of noise… it is only in cases in which excessive noise could have been avoided by the exercise of reasonable care on the part of the driver that the police have power to take action against the driver”.

A second example is as illustrated in a series of letters of 1938,The National Archives, 1949 between UK Government departments, the Berkshire Constabulary and Wokingham Council, whereby regulations were not considered to be effective in relation to noise. A leisure area known as “California in England” attracted “a very heavy traffic, comprising chars-a-banc, motor cars and motor cycles”. The police was unable to penalise individual vehicles which had been unduly noisy since the issue was that “vehicles arrive and leave in batches (NB which) increases the volume of noise. The police have not observed cases of dangerous riding or excessive speed”.

A feature of the regulations introduced above is the absence of any type of limits. To incorporate limits to the different parts of a car producing noise, three reports were commissioned by the Departmental Committee on Noise in the Operation of Mechanically Propelled Vehicles (the Kaye commission).The National Archives, 1949 The first report of 1935 versed on the units of, instrumentation types, methods of measurement, different types of microphones and weighting curves.Kaye, 1935 It introduced the need for “the use of ‘objective noise meters’ which should be tested, calibrated and approved”. An interesting observation made in the report is that “While universality of application cannot at present be claimed for such instruments, their convenience may often outweigh their theoretical imperfections.”

The articles published in local newspapers about the publication of the first report confirm the introduction of objective noise measurements in detriment of aural judgements. The articles also illustrate two elements that will be recurrent and still present nowadays:

- The introduction of a noise limit per vehicle in addition to the speed limit: “90 phons of noise when running at 30 m.p.h.” at a lateral point 18 feet from the vehicle, representative of the average location of “persons on the footway of a road”.

- The difficulty of ensuring that a unit as the phon (or nowadays the decibel) is understandable by the public. Thus, the proposed noise limits were compared to the 90 phons of noise in a busy typing office or the 90–95 phons at the interior of a tube train with open windows.

A second reportKaye, 1936 only addressed new vehicles and only minor changes were made to the first report.Kaye, 1935 A further report was issued in March 1937Kaye, 1937 , which recommended noise limits also for vehicles already in use. On the comments to the tests undertaken it confirmed that instruments gave a reliable reading in comparison to an “aural impression”.

Although the issue with noise related to motor and exhausts had partially been addressed, the problem with the use of electric horns remained. Suggestions were made in order to prohibit “the use of a super-charges … just as cut-outs are forbidden.” The report continued: “Complaints with regard to noise caused by motor vehicles are generally directed towards inadequate silencers, noise mechanism of the vehicle, noisy loads, or the use of excessively strident motor horns, or the excessive use of motor horns by drivers. On all these subjects, except stridency of motor horns, provision has been made in the Motor Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations, 1931”.The National Archives, 1949

As published in the Motoring Correspondent, 1939 and the Times Morning Post, 1939The National Archives, 1949 , the UK Government’s Minister of Transport reached an agreement with the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders to limit the loudness of most horns to 100 phons. The newspaper article highlighted that “Because of the successful outcome of the negotiations the Minister has decided not to proceed for the time being with the making of regulations which would impose a compulsory limit on the loudness of horns.”.

3.8. Aircraft noise and statutory defence

After WWII, when noise from rail and road had already been addressed, the British jet industry took off thus incorporating a further noise source into the environment. To protect this emergent industry, the Civil Aviation Act 1949 sections 40 and 41UK Parliament, 1949 abolished the right of civil actions where regulations under the act were made. The Government removed a fundamental right and moreover did not allow for compensation.

Aircraft operators were protected by Orders and Regulations under the Act from an early stage. The same immunity was given to aircraft manufacturers after a complaint by the owner of a farm next to Dunsfold airfield, near Guildford, could have stopped the works of Hawker Aircraft Company.Brook, 1954, UK Government, 1954a, UK Government, 1954b Aircraft noise continued to be a problem since the “new big jet aircraft” was introduced in the late 1950 s —see reference to Boeing 707–120 and to Soviet TU.104 in UK Government, 1958 or to the “supersonic Concorde” of the mid 1970’s.UK Government, 1976, UK Government, 1969 The compromise in each case was to allow noisy aircraft with the hope that technical advance would reduce noise levels in the future. In the case, of the Soviet TU.104 potential time restrictions were discussed. On the 1954 Hawker Aircraft Company case, the Cabinet meetings recorded the following two points:UK Government, 1954a

(b) Criticism might well be directed in the debate against the drastic provisions of sections 40 and 41 of the Civil Aviation Act, 1949. These sections had abolished the right to bring an action for nuisance in any case which was covered by an Order in Council made under the Act, and had also provided that no compensations should be payable in this connection.

(c) It would be undesirable to reopen the way to any form of compensation in cases of this kind, since this would expose the Government to numerous claims in respect of R.A.F airfields and possibly airfields in use by the United States Forces.

3.9. The Noise Abatement Act 1960, the Wilson Committee, the Scott Committee and the entrance to the European Economic Community

The recurrent concern to the cost of noise mitigation is highlighted in the following sentence from a UK Cabinet meeting in relation to the establishment of a future committee on noise:UK Government, 1959 “There was some pressure on the Government, both in and outside Parliament, to take action for the abatement of noise; and, in view of this and of the complexity of the problem, there was a good case for the appointment of a committee of enquiry… Discussion showed that there was a general agreement with this proposal. The danger that the committee might make recommendations which would prove unduly expensive might be mitigated by care in securing a suitable chairman…”. The Noise Abatement Act 1960UK Parliament, 1960 made noise (a nuisance in common law) a statutory nuisance for the first time under the Public Health Act 1936.UK Parliament, 1936 The Public Health Acts of 1848 and 1875UK Parliament, 1875, UK Parliament, 1848 defined certain matters as being “a nuisance or injurious to health”. In the Public Health Act 1936, this was reworded as “a nuisance or prejudicial to health”. However, noise was only specifically cited as a form of “nuisance” into the Noise Abatement Act, 1960. The Environmental Protection Act 1990 defined noise as being “prejudicial to health or a nuisance” in line with the advice in the World Health Organization’s Environmental Health Criteria 12.WHO, 1980

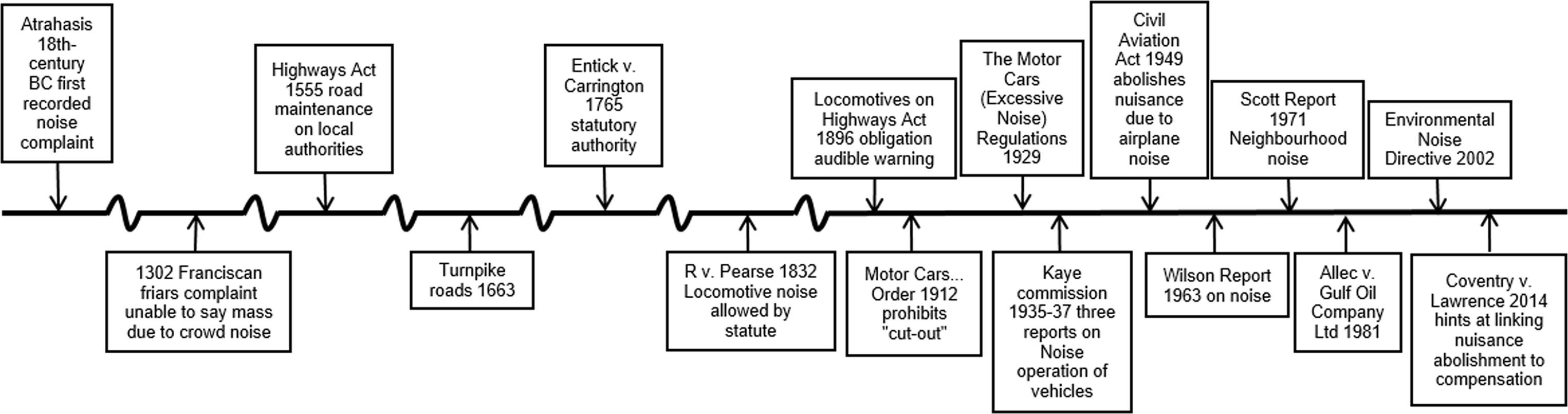

Current noise policy in England includes a similar distinction between “quality of life” effects (subjective) and “health effects”, and differentiates between adverse and significant adverse effects.Defra, 2010, MHCLG, 2021a, MHCLG, 2019 . After the first departmental committee on traffic noise in the 1930 s, two further committees were created in the 1960 s and 1970 s: the Wilson committee on Noise,Wilson, 1963 which favoured the inclusion of technical input within environmental noise legislationLucas, 1989 and also advised that grants should be made, subject to specific conditions, towards the cost of insulating houses in the neighbourhood of airportsKerse, 1975 , and the Scott committee on Neighbourhood noise,Kerse, 1975, Lucas, 1989 citing Noise Advisory Council, 1971 which drafted part of the noise section of the Control of Pollution Act 1974.Kerse, 1975, Lucas, 1989 Part of the recommendations of both committees, such as the definition of noise limits for certain industrial machinery and construction plant were finally implemented through the transposition of European Community legislation.Lucas, 1989 . More recently, the UE’s Environmental Noise Directive introduced the need for managing existing issues from noise arising from road, rail, aircraft and industry. This process involved the production of strategic noise maps to identify the most affected areas as well as the areas that should be subject of protection due to their quietness and the production of noise action plans to address noise issues.European Commission, 2016, European Parliament, 2002 . Figure 1 shows the timeline with the main events discussed in this article.

4. Conclusions

Atrahasis’ epic shows that noise (and its mitigation) is not a recent occurrence —it was already present in antiquity, at least as early as urban societies appeared. In England, nuisance in common law has been dealing with noise since medieval times. To understand the evolution in the law of noise, this paper has approached two main questions. The first, whether the current interpretation of the law of noise is the same as its original intent. Railways provide the primary example to affirm that the law of noise has remained notably stable over time. The findings of the first railway case, R v. Pearse (1832) were still vindicated in Allen v. Gulf Oil Refining Ltd 1981, which reviewed the law of nuisance in relation to enterprises approved by a Private Act. The second matter addressed in this paper is that the same laws do not apply to all forms of transport. Railways, roads and aircraft are all of significant economic importance. They were put in one way or another under the protection of statutory authority, which in practice restricted rights existing in common law, such as the right to raise a claim on nuisance grounds. However, the tools to make a claim are different for each of these means of transport.

Unlike road and aircraft noise, the statute (the Environmental Protection Act 1990 as amended) does not specifically provide railway noise with statutory protection against nuisance claims. Nevertheless, common law allows a defence of statutory authority to railways, the reason being that railways were allowed through Private Acts. The defence of statutory authority applied to railways is still the model for cases of nuisance related to all types of enterprises allowed through a Private Act. The defence applied to railways evolved from the same defence applied to turnpike roads and at the same time the defence applied to turnpike roads evolved from some medieval precedents likely to be related to mining and, roads and bridges maintenance. Defence of statutory authority is linked to a test of reasonable care.

Conversely, road traffic and aircraft enjoy statutory protection against nuisance claims. Deprived of common law remedies – such as injunction and damages –, policy tools come on stage. In this vein, Moor (2011) claims that “Parliament has […] been quite reluctant to show a clear and explicit intention to remove citizen’s private rights, and express statutory authority has appeared in very few legislative provisions… Where immunity has been awarded, it has generally only been successfully received when juxtaposed with some form of statutory remedy”. For instance, through the Land Compensation Act 1973. However, in the same way as the courts accord a similar meaning to the expression nuisance in its statutory context, as they do to its meaning at common law,Adams and McManus, 1994 compensation has been extended to railway schemes. This is the case of The Noise Insulation (Railways and Other Guided Transport Systems) Regulations 1996 developed in line with section 20 of the Land Compensation Act 1973. Even if railways are not specifically mentioned in the Act, public works may be interpreted flexibly. Current legislation and policy incorporate a distinction between different categories of noise effects: nuisance or prejudicial to health, quality of life or health effects, and adverse or significant adverse effects.Defra, 2010, MHCLG, 2021a, MHCLG, 2019 Guidance describes potential effects as a consequence either of changes in noise levels compared to a prevailing acoustic environment, or as absolute noise levels – the latter usually related to loud noises.MHCLG, 2019 All these distinctions assist to address the requirements under the Environmental Impact RegulationsUK Parliament, 2017 which separately identify nuisances and risks to human health.

Further research and future evolution in law is likely to approach the following areas:

- The economic element of the suppression of actions on nuisance. Either through direct compensation, or encouraging innovation in noise mitigation and abatement beyond the requirement of reasonable care. The need for compensation in exchange for a statutory defence is not yet conclusive. However, a trend seems to exist in that direction.UK Government, 1996, UK Government, 1975, UK Parliament, 1973, Neuberger et al., 2014 In relation to industries, such as railways, that enjoy a defence of statutory authority, one could question if the test of reasonable care (or lack of negligence) is limiting innovation in nuisance mitigation and abatement, which would likely occur if the law required a fixed part of the operating budget be intended for research. Even more at a time when simulation (usually cheaper than the construction of pilot machinery or plant) is commonplace in the mechanical industry.

- The distinction between noise as a nuisance and noise as prejudicial to health. “It is acknowledged that further research is required to increase our understanding of what may constitute a significant adverse impact on health and quality of life from noise.”Defra, 2010

- Whether it is worth retaining different legislative and regulatory approaches to different types of noise sources. This is also relevant considering that new noise sources such as wind farms or drones have been introduced in the acoustic environment recently, and their presence is likely to increase gradually. The current policy and regulatory frameworks contain a mix of tools which address all types of noise in the same wayEuropean Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2002 and others which retain a different approach depending on the type of noise.UK Parliament (1990) —also WHO (2018) which provides noise thresholds and targets based on the noise source rather than based primarely on the type of noise sensitive receptor as previously Berglund et al, 1999

- Soundscaping, which is defined as the combination of sounds that form an immersive environment, is currently being introduced in policy guidance.MHCLG, 2021b, MHCLG, 2019 Research may be necessary to define whether soundscaping requirements are already present in law or need to be specifically incorporated, as these could form an interesting counterpoint to define nuisance in a localised context.

Acknowledgements

JS would like to thank Dr Joan Jorge for his support and encouragement during all the research process.

References

Abbott et al., 2015 Abbott, P., Berry, B., Hansell, A., Laszlo, H., McKell, B., 2015. Possible Options for the Identification of SOAEL and LOAEL in Support of the NPSE. Glasgow. https://doi-org.recursos.biblioteca.upc.edu/10.13140/RG.2.1.2000.3921, Google Scholar

Adams and McManus, 1994 M.S. Adams, F. McManus. Noise and Noise Law. A Practical Approach. Wiley Chancery Law, London (1994) Google Scholar

Alexander and Siton, 2018 C. Alexander, A. Siton. The Stephenson Railway Legacy. Amberley Publishing (2018). Google Scholar

Bassford, 2007 H. Bassford. Major infrastructure projects - The answer is the planning white paper. Now, what was the question? J. Plan. Environ. Law (2007), pp. 134-157. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Berglund and Lindvall, 1995 Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., 1995. Community Noise. Google Scholar

Berglund et al., 1999 Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., Schwela, D.H., 1999. Guidelines for Community Noise. Google Scholar

Boughey and Hadfield, 2012 Boughey, J., Hadfield, C., 2012. British Canals: The Standard Story, Kindle Edi. ed. The History Press. Google Scholar

Brenner, 1974 J.F. Brenner. Nuisance Law and the Industrial Revolution J. Legal Stud., 3 (2) (1974), pp. 403-433. CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Brook, 1954 Brook, S.N., 1954. The National Archives’ reference CAB 195/12/33. Google Scholar

Brubaker, 1995 Brubaker, E., 1995. The Defence of Statutory Authority, in: Property Rights in the Defence of Nature. Earthscan Publications Limited and Earthscan Canada. Google Scholar

Casciani, 2021 D. Casciani What is the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill and how will it change protests? BBC News (2021) (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-56400751) (accessed 9.21.21), Google Scholar

Cooper, 2006 A. Cooper Bridges, Law and Power in Medieval England. Boydell Press (2006), pp. 700-1400. CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Defra, 2010 Defra, 2010. Noise Policy Statement for England (NPSE). Department for Communities and Local Government, London [WWW Document]. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69533/pb13750-noise-policy.pdf (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

European Commission, 2016 European Commission, 2016. Evaluation of Directive 2002 / 49 / EC relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise. Appendices. Brussels [WWW Document]. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/noise/pdf/study_evaluation_directive_environmental_noise_appendices.pdf (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

European Commission, 2016 European Commission, 2016. REFIT Evaluation of the Directive 2002/49/EC relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise. https://doi-org.recursos.biblioteca.upc.edu/10.2779/171432. Google Scholar

European Parliament, 2002 European Parliament, Council of the European Union, 2002. Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise. Google Scholar

García, 2006 A. García. La contaminación acústica: fuentes, evaluación, efectos y control Sociedad Española de Acústica (2006), pp. 14-15. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Gearty, 1986 C.A. Gearty. The role of the courts in the control of environmental pollution: A legal and historical analysis. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge (1986). Google Scholar

Gimpel, 1976 Gimpel, J., 1976. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Google Scholar

Goodman, 1961 Leo A. Goodman. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat., 32 (1) (1961), pp. 148-170, 10.1214/aoms/1177705148 CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Henry, 1912 Henry, E.R., 1912. The National Archives’ reference MEPO-4-295. London. Google Scholar

Jeans, 1875 Jeans, J.S., 1875. Jubilee Memorial of the Railway System. A history of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and a record of its results. Longmans, Green and Co., London. Google Scholar

Kaye, 1935 Kaye, G.W.C., 1935. First Interim Report of the Departmental Committee on Noise in the Opetation of Mechanically Propelled Vehicles (NB within The National Archives reference HO 45/23019 Traffic: Nuisance of noise from motor vehicles). London. Google Scholar

Kaye, 1936 Kaye, G.W.C., 1936. Second Interim Report of the Departmental Committee on Noise in the Opetation of Mechanically Propelled Vehicles (NB within The National Archives reference HO 45/23019 Traffic: Nuisance of noise from motor vehicles). London. Google Scholar

Kaye, 1937 Kaye, G.W.C., 1937. Third Interim Report of the Departmental Committee on Noise in the Operation of Mechanically Propelled Vehicles (NB within The National Archives reference HO 45/23019 Traffic: Nuisance of noise from motor vehicles). London. Google Scholar

Kerse, 1975 C.S. Kerse. The Law Relating to Noise. (First edit. ed.), Oyez Publishing, London (1975) Google Scholar

Kirby, 1993 M.W. Kirby. The origins of railway enterprise: the Stockton and Darlington Railway 1821–1863. Cambridge University Press (1993) Google Scholar

Lambert and Millard, 1968 W.G. Lambert, A.R. Millard. Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood (with “The Sumerian Flood-story” by M. Civil). Clarendon Press, Oxford (1968). Google Scholar

Langdon and Claridge, 2011 J. Langdon, J. Claridge. Transport in Medieval England. Hist. Compass, 9 (2011), pp. 864-875, 10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00804.x CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Linden, 1966 A.M. Linden. Strict Liability, Nuisance and Legislative Authorization. Osgode Hall Law J., 4 (1966), pp. 196-221. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Lucas, 1989 P.H. Lucas. Science in legislation and its enforcement: A study of neighbourhood noise. University of London (1989) Google Scholar

Lyman, 1964 J.L. Lyman. The Metropolitan Police Act of 1829. J. Crim. law Criminol., 55 (1964), pp. 141-154. CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Macauley, 1872 Macauley, J., 1872. The late Joseph Pease. Leis. hour a Fam. J. Instr. Recreat. 375–379. Google Scholar

MHCLG, 2019 MHCLG, 2019. Planning practice guidance on Noise to the National Planning Policy Framework. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/noise\--2 (accessed 8.29.21). Google Scholar

MHCLG, 2021a MHCLG, 2021a. National Planning Policy Framework. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1005759/NPPF_July_2021.pdf. Google Scholar

MHCLG, 2021b MHCLG, 2021b. National Design Guide. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Available on https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/962113/National_design_guide.pdf. Google Scholar

Millard, 1966 A.R. Millard. The Atrahasis Epic and Its Place in Babylonian Literature. University of London (1966). Google Scholar

Moor, 2011 Francis Moor. Planning for nuisance?: A review of the effects of the Planning Act 2008 on the statutory authority defence in the UK. Int. J. Law Built Environ., 3 (1) (2011), pp. 65-82, 10.1108/17561451111122615 CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Moran, 1971 W.L. Moran. Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Biblica, 52 (1971), pp. 51-61. View Record in Scopus{.link}Google Scholar

Morgan, 2014 J. Morgan. Technological Change and the Development of Liability for Fault in England and Wales. M. Martin-Casals (Ed.), The Development of Liability in Relation to Technological Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2014), p. 275. Google Scholar

Motoring Correspondent, 1939 Motoring Correspondent, 1939. Noise Limit for Motor Horns. Makers’ Pledge (within The National Archives reference HO 45/23019). Dly. Telegr. Morning Post. Google Scholar

Neuberger et al., 2014 Neuberger, Lord, Mance, Lord, Clark, Lord, Sumption, Lord, Carnwath, Lord, 2014. JUDGMENT Coventry and others (Respondents) v Lawrence and another (Appellants) (No 2). Google Scholar

Newman, 2012 Newman, S., 2012. Transportation in the Middle Ages [WWW Document]. https://www.thefinertimes.com/transportation-in-the-middle-ages (accessed 7.13.20). Google Scholar

Noise Advisory Council, 1971 Noise Advisory Council. Neighbourhood Noise. A Report by the Working Group on the Noise Abatement Act (Chairman: Sir Hilary Scott), HMSO, London (1971). Google Scholar

Oden, 1981 R.A.J. Oden Divine Aspirations in Atrahasis and in Genesis 1–11. Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wiss., 93 (1981), pp. 197-216. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Pease, 1907 E. Pease. The Diaries of Edward Pease. The father of English Railways. (Digitally. ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1907). Google Scholar

Smith and Wilde, 2010 Smith, C., Wilde, M., 2010. R v Pease (1832), in: Mitchell, C., Mitchell, P. (Eds.), Landmark Cases in the Law of Tort. Hart, Oxford, pp. 1–31. Google Scholar

Tempest and Bryan, 1976 W. Tempest, M.E. Bryan. Noise measurement and evaluation. Proc. Inst. Electr. Eng., 123 (10R) (1976), 10.1049/piee.1976.0208 Google Scholar

The Guardian, 1891 The Guardian, 1891. Eastbourne Riots. Guard. pag. 6 https://www.newspapers.com/clip/22575829/eastbourne-riots/ (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

The National Archives, 1302 The National Archives, 1302. Petitioners: Friars Minor (Franciscans) of Bury St Edmunds. Addressees: King https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C9060133 (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

The National Archives, 1895 The National Archives, 1895. The National Archives' reference HO 45/9901/B19330. Bye-Laws: Copies submitted to Secretary of State 1883-1886 re Noises in Streets, Processions, etc. Google Scholar

The National Archives, 1949 The National Archives, 1949. The National Archives reference HO 45/23019 Traffic: Nuisance of noise from motor vehicles. Google Scholar

Times Morning Post, 1939 Times Morning Post, 1939. Noise Limit for Motor Horns. Makers Agreement with Ministers (within The National Archives reference HO 45/23019). Times Morning Post. Google Scholar

UK Government, 1954a UK Government, 1954a. The National Archives’ reference CAB 128/27/44. Google Scholar

UK Government, 1954b UK Government, 1954b. The National Archives’ reference CAB 129/69/13: Noise at Airfields. Memorandum by the Minister of Supply and the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation. London. Google Scholar

UK Government, 1958 UK Government, 1958. The National Archives’ reference CAB 129/94/22: Civil Aviation: Jet Aircraft Noise. Memorandum by the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation. London. Google Scholar

UK Government, 1959 UK Government, The National Archives’ reference CAB 128/33/61: Noise Abatement, The National Archives (1959). Google Scholar

UK Government, 1969 UK Government, 1969. The National Archives’ reference CAB 129/143/17: Commecial Supersonic Flying and Airport Noise of Concorde. Note by the President of the Board of Trade. London. Google Scholar

UK Government, 1975 UK Government, 1975. The Noise Insulation Regulations 1975. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1975/1763/contents/made (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

UK Government, 1976 UK Government, 1976. The National Archives’ reference CAB 128/58/1 Cabinet meeting minutes 15 January 1976. Google Scholar

UK Government, 2021 UK Government, 2021. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. UK Parliament. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1555 UK Parliament, 1555. Highways Act 1555. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1829 UK Parliament, 1829. Metropolitan Police Act. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1839 UK Parliament, 1839. Metropolitan Police Act. London. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1848 UK Parliament, 1848. An Act for promoting the Public Health. UK Parliament, London. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1861 UK Parliament, 1861. The Locomotive Act 1861. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1865 UK Parliament, 1865. The Locomotive Act 1865. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1875 UK Parliament, 1875. Public Health Act. URL https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/38-39/55/enacted. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1882 UK Parliament, 1882. Municipal Corporations Act. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1896 UK Parliament, 1896. The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1936 UK Parliament, 1936. Public Health Act. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1949 UK Parliament, 1949. Civil Aviation Act 1949. UK Parliament, London. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1960 UK Parliament, 1960. Noise Abatement Act. Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1973 UK Parliament, 1973. Land Compensation Act 1973. URL https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1973/26/contents (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 1990

UK Parliament, 1990. Environmental Protection Act 1990.

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/43/contents (accessed

9.21.21).

Google

Scholar

UK Government, 1996 UK Government, 1996. The Noise Insulation (Railways and Other Guided Transport Systems) Regulations 1996. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1996/428/contents/made (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 2010a UK Parliament, 2010a. Living Heritage. Roads and Railways. Turnpikes and tolls. UK Parliam. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/transportcomms/roadsrail/overview/turnpikestolls/ (accessed 5.2.20). Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 2010b UK Parliament, 2010b. Living Heritage. Roads and Railways. Fire and steam. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/transportcomms/roadsrail/overview/fireandsteam/ (accessed 8.29.20). Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 2010c UK Parliament, 2010c. Living Heritage. Roads and Railways. Private Acts. UK Parliam. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/transportcomms/roadsrail/overview/privateacts/ (accessed 5.2.20). Google Scholar

UK Parliament, 2017 UK Parliament, 2017. The Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/572/contents/made (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

Webb and Webb, 1913 Webb, S., Webb, B., 1913. English Local Government: The Story of the King’s Highway. Longmans, Green and Co., London. Google Scholar

WHO, 1980 WHO, 1980. Environmental Health Criteria 12. Noise. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39458 (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

WHO, 2009 WHO, 2009. Night noise guidelines for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/43316/E92845.pdf (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

WHO, 2018 WHO, 2018. Environmental noise guidelines for the European Region. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/383921/noise-guidelines-eng.pdf (accessed 9.21.21). Google Scholar

Wilde, 2017 M.L. Wilde. All the Queen’s horses: Statutory authority and HS2. Leg. Stud., 37 (4) (2017), pp. 765-785, 10.1111/lest.12173 CrossRef. View Record in Scopus, Google Scholar

Willberforce et al., 1980 Willberforce, Lord, Diplock, Lord, Edmund-Davies, Lord, Keith of Kinkel, Lord, Roskill, Lord, 1980. Allen v Gulf Oil Refining Ltd [1980] UKHL 9. Google Scholar

Wilson, 1963 Wilson, A.H., 1963. The National Archives, Kew, Reference MH 146/285. Committee on the problem of noise. Final report - Copy and proofs. Google Scholar